Human and Machine: A Journey - Part 3

Navigating Between National Guidelines and Local Practice

In our previous explorations, we examined the philosophical landscape of welfare systems and delved into how modern society's machinery evolved from the social contract. We saw how complex networks of institutions, bureaucracies, and technological systems have emerged to serve society's needs. Now, let's explore the crucial intersection where national guidelines meet local practice – where the map meets the terrain.

The Necessity of Maps

Just as early civilizations created maps to navigate their physical world (from simple cave paintings in Çatalhöyük around 6200 BC to the sophisticated geometric systems of ancient Greece), modern welfare systems need "maps" – guidelines, frameworks, and systems – to navigate increasingly complex social landscapes. These aren't mere suggestions; they're essential tools for ensuring equity, legal security, and evidence-based practice. Yet, like all maps, they are representations of reality, not reality itself.

When Systems Meet Reality

Consider Sweden's child welfare implementation of BBIC, adapted from the British Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (FACNF). This system offers a fascinating case study of what happens when formal systems encounter practical reality. In the journey from national guidelines to local implementation across 290 municipalities in Sweden, BBIC has undergone multiple "translations." Each municipality has had to integrate and adapt the system to their context.

The result is paradoxical and complex. The British framework was originally grounded in extensive research synthesis and best practices, particularly around attachment theory, trauma, and child welfare interventions. Yet in its Swedish implementation, something significant happened: while the system has created increased unity in documentation practices and assessment procedures, it has simultaneously led to increased variation in how social workers actually engage with families and children.

This transformation reveals important questions about system implementation. The process of adapting such comprehensive frameworks across different cultural and organizational contexts inevitably involves trade-offs and transformations. While the system has brought important benefits in terms of structured assessment and documentation, it has also led to new challenges in balancing administrative requirements with direct client work.

This paradox illustrates a fundamental tension in modern welfare work – not just the balance between standardization for equity and flexibility for individual adaptation and assessment, but also between systematic methodology and human engagement. It raises important questions about how we can preserve the essence of social work while still benefiting from structured approaches and standardized methods.

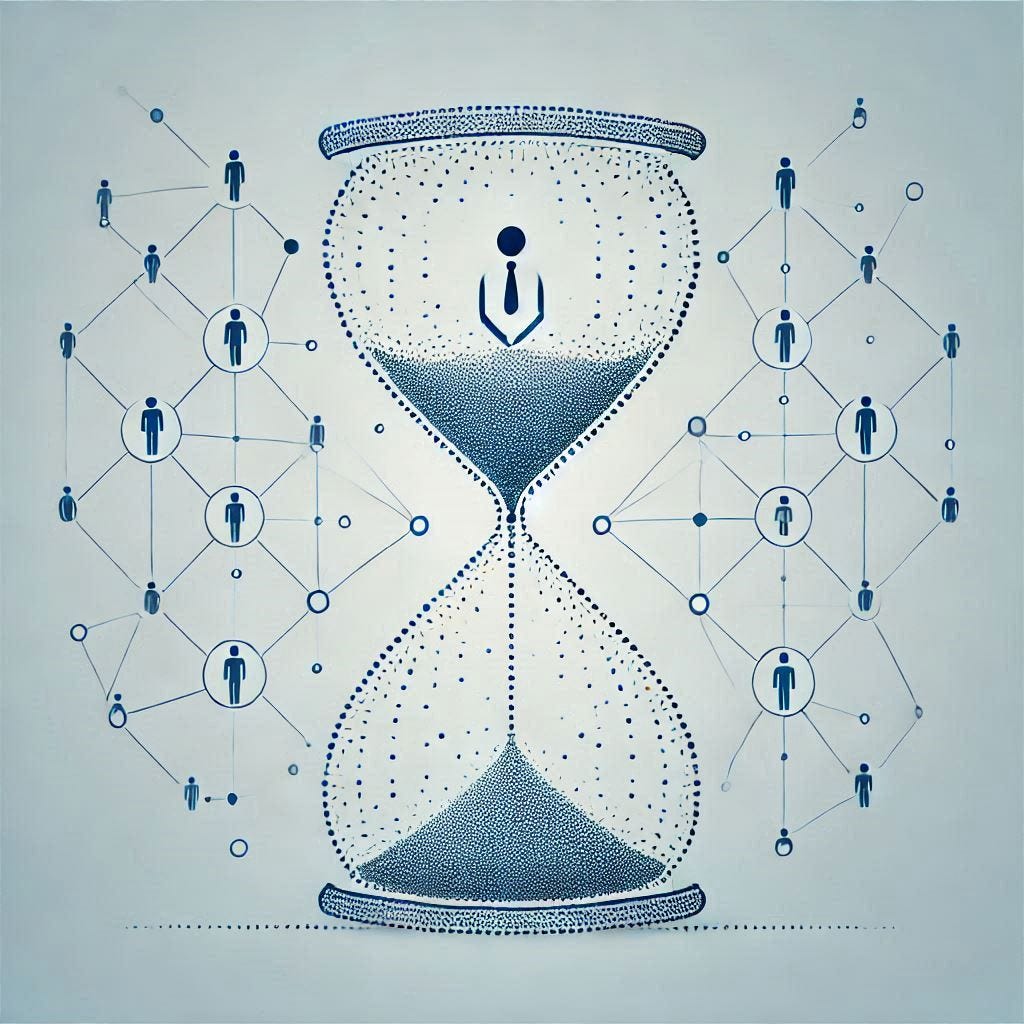

The Hourglass of Knowledge Flow

In understanding how knowledge moves between national guidelines and local practice, we might imagine an hourglass structure. At the top, we find two types of actors:

The Analysts

Researchers studying frontline practice

Academics developing theoretical frameworks

Evaluators assessing program outcomes

The Directors

Policy makers developing guidelines

Agencies issuing regulations

Organizations setting standards

At the bottom of the hourglass, we find the practitioners and their daily operations - where theory meets reality, where guidelines encounter individual cases, where standardized methods face unique circumstances. This is where knowledge becomes action, where abstract principles transform into concrete interventions.

The narrow middle of the hourglass represents the delicate process of knowledge translation - how research findings become practical guidelines, how frontline experiences inform policy development, how theoretical understanding shapes actual practice. This translation requires careful attention to different types of knowledge:

Scientific evidence from systematic reviews

Practice-based knowledge from experienced professionals

Contextual knowledge about local conditions

Experiential knowledge from service users

Understanding this structure helps us appreciate why implementation is so complex and why leaders in welfare need a broad knowledge. Knowledge doesn't simply flow from top to bottom - it needs to move in both directions, with practitioners' experiences informing analysis and direction just as much as research and policy guide practice. The challenge lies in creating systems that facilitate this two-way flow while preserving the integrity of each knowledge type.

The Evolution of Systematic Knowledge

The journey toward evidence-based practice in social services closely parallels developments in medicine, particularly in how we synthesize and evaluate research. As Bohlin (20121) details in his analysis of the historical development of research synthesis, Meta-analysis, first developed in social sciences in the 1970s before being adopted by medicine in the 1980s, represents a crucial advancement in how we build systematic knowledge.

Before meta-analysis, knowledge synthesis largely relied on narrative reviews, where experts would qualitatively summarize existing research. While valuable, these reviews could be subjective and struggled to handle large volumes of research systematically. Meta-analysis introduced formal, quantitative methods for combining results across multiple studies, treating the synthesis of research with the same rigor as primary research itself.

This evolution culminated in the development of systematic reviews in the early 1990s, which provided a broader framework that could include, but didn't require, meta-analysis. This approach to knowledge synthesis has become fundamental to evidence-based practice, offering a structured way to evaluate and combine different forms of evidence. The establishment of the Cochrane Collaboration in 1993 marked a crucial turning point, creating an international network dedicated to producing and disseminating high-quality systematic reviews of healthcare interventions.

Cochrane's famous logo, showing a forest plot of seven clinical trials examining the effectiveness of corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth, powerfully illustrates how meta-analysis can reveal clear evidence (the ◆-shape) of benefit (in this case, that the treatment reduced infant mortality) even when individual studies were too small to show definitive results.

However, while these tools are invaluable for building our knowledge base, they remind us of an important truth: even the most rigorous synthesis methods must eventually meet the complexity of real-world practice. The challenge isn't just in developing good evidence, but in translating it into meaningful practice while preserving professional judgment.

The Multi-Layered Challenge of Translation

When we talk about translating knowledge into practice, we often think of it as a simple, linear process - take the evidence and implement it. But reality is far more complex, especially in welfare services. The sociologist Harry Collins made a fascinating observation about how distance affects our understanding in science - the further removed we are from the actual production of knowledge, the more certain and unambiguous things appear. He called this phenomenon "distance lends enchantment."

Think about standing on a mountaintop looking down at a city. From that distance, the patterns become clear - you can see how neighborhoods connect, how traffic flows, where green spaces break up the urban landscape. This perspective is invaluable for urban planning. Yet, from that same distance, you can't see the local challenges - the pothole that residents navigate daily, the unofficial shortcut that everyone uses, the community garden that brings neighbors together.

This same dynamic plays out in our welfare systems. At the top of our hourglass, analysts and directors work with a certain distance from practice - and this distance both helps and complicates their work. As Collins noted, when we're closer to events, we see more contingencies and hidden factors, making clear judgments harder. But that complexity is crucial information. The analysts processing systematic reviews must juggle multiple perspectives:

Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Health economic considerations about resources and costs

Ethical implications for different stakeholder groups

System-level impacts and organizational readiness

Each layer of analysis adds distance from practice, and with that distance comes both clarity and potential distortion. The health economist might see clear cost-effectiveness patterns that were invisible to practitioners, while missing crucial implementation barriers that are obvious on the ground. The ethicist might identify important value conflicts that practitioners navigate intuitively every day.

This tension between distance and proximity is particularly evident in how Sweden implemented BBIC. The journey from British research to Swedish national guidelines to local implementation across 290 municipalities shows how each translation step required balancing the clear view from afar with the complex reality on the ground. What appears as straightforward best practice in a systematic review can encounter unexpected challenges when meeting local conditions.

Strategic Use of Distance and Proximity

This interplay between distance and proximity isn't just an unavoidable fact - it's a tool we can use strategically in welfare services. Sometimes we need trust and flexibility, which calls for proximity - delegating responsibility and authority to those closest to the work. Other times we need control and limitations, where distance serves an important function of oversight and standardization.

The same principle applies to guideline development. Sometimes we need to make recommendations even when evidence is scarce. In these cases, ethical analysis might suggest that an intervention should or shouldn't be done, even without strong evidence. The key then becomes focusing on HOW the intervention is carried out rather than just WHETHER it should be done.

This is particularly relevant in social services, where we often face situations where guidelines are lacking due to limited evidence, yet tasks must still be performed according to law. How do we navigate this? (And here's a spoiler alert: Autonomy and self-determination emerge as crucial principles in social work when we serve as guardians of the social contract).

It's a delicate balance: maintaining enough distance to see patterns and ensure equity, while staying close enough to understand individual needs and contexts. This balance becomes especially critical when we're working with limited evidence but mandatory responsibilities. It's in these situations that our role as guardians of the social contract becomes most apparent - we must find ways to fulfill our obligations while respecting fundamental principles of autonomy and self-determination.

In our next post, we'll explore how tacit knowledge - the kind that comes from years of practice and can't easily be written into guidelines - plays a crucial role in this translation process. But for now, consider: How do you use both distance and proximity in your own practice? When does stepping back help you see more clearly, and when does getting closer reveal crucial details?

This is part 3 in our ongoing series exploring the intersection of human judgment and systematic knowledge in modern welfare systems. Join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

in "Formalizing Syntheses of Medical Knowledge: The Rise of Meta-Analysis and Systematic Reviews". Perspectives on Science (2012), vol. 20, no. 3 ©2012 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.